|

|

|

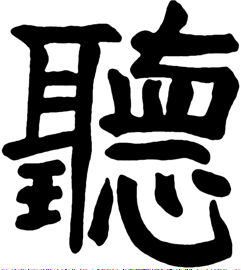

JANUARY 1, 2015 Let's re-cap on those 2014 musical resolutions. In short, I accomplished one-third of my goal. I guess it's better than nothing. Resolutions rarely work out as I planned. The river of my life often tends to follow different streams, and I go with the flow. On the plus side, I did create three new vocal compositions. One of them (The Lord Is My Shepherd) will be performed for the Greater Westfield Choral Association concert on March 15. And I've begun work on a full choral mass, which I'll be submitting to GWCA for their 40th anniversary season. I also created two new pieces as soundtracks for the animation class I teach at HCC. Although I've enjoyed creating those pieces, I've been disappointed with the end result of their intended function. I used to have students create silent animations, and give students general freedom to pick their own topics. What I discovered was that most students would complete less than 30 seconds of a two or three minute piece. The main complaint I heard was that they couldn't think of anything to do. So I decided to create a theme for each animation (which changes each semester) and give them a rhythmic soundtrack to help them animate. Now students generally turn in less than 30 seconds of work. So it doesn't seem to matter if I take the time to create the music; it doesn't seem to help at all. I just chalk it up to yet another manifestation of the college's policy to admit anyone, whether they've qualified for college-level work or not. I'll probably continue with the music anyway, simply because I enjoy it and it motivates me to create. Our church is entering another period of change. Our pastor has decided to move on, effective today. So we're entering a phase where the deacons (including me) will be in charge of the worship services. I'll be delivering a sermon in a few weeks. And I'll probably be part of the committee that searches for a new pastor. Meanwhile, I've also taken over the church's website and have gradually begun modifying it. That will be a never-ending process. But again, it helps me be creative and also keeps me exploring Web technologies. The year ahead is already filling up. I'm continuing as editor of the Western New York Coaster Club's Gravity Gazette™, creating an issue each month. I'm sure there will be several amusement park trips. I'm really curious about the re-built of the infamous Cyclone at Six Flags New England. The annual Railroad Hobby Show will be coming up in a few weeks. I'm still planning the expansion of my own railroad layout, so maybe I'll get some ideas at the show. I've begun the lengthy process of arranging my finances for retirement. It's hard to believe that I'm heading rapidly and inexorably into senior citizen territory. There's a certain comfort in knowing that in the not-too-distant future, I'll have every day wide open to fill with whatever I want. But I know full well that nature abhors a vacuum; when I have all the time in the world, the demands on my time will no doubt increase exponentially. I still wonder how I cranked out so much writing when I was younger. There wasn't any more time in the day, and I also had jobs and was going to school. And yet it was the most prolific period of my life. This year marks the twentieth anniversary of my final solo recording, Piano Works. As I look back through squinty eyes at that achievement, I'm also focusing ahead on the long-delayed third recording by Karen and me, Moonlight Serenade. I found some of the original test recordings we made nearly a decade ago. I know there are more of them somewhere, but "where" is anybody's guess. It wouldn't be much trouble to re-record the selections. As with everything else, it's just a matter of setting aside the time. Let's see if it happens in 2015.... JANUARY 11, 2015 Epiphanies on Demand

It was a quiet night, sitting in my little den. I was hunched over my computer, its glow bathing my face. I was struggling to complete a piece of music. My eyes were bleary. I had begun writing the piece, a choral hymn based on Psalm 23, nearly two years before. But I hit a wall. I had the beginnings of a melody line for the sopranos, but I couldn’t figure out how to finish it. So after those two years, I had finally realized the problem: I had created the piece with the wrong time signature. I had been trying to cram the verse into an unnatural rhythm. I don’t know why I hadn’t thought of that earlier, but once I changed the time signature, the vocal parts poured out in a sort of mental flood. I struggled to write the notes down fast enough. In one evening, all the vocals were finished, and over the following month I tweaked and refined them. But there was one thing missing: I had no accompaniment. As with my original attempt at the vocals, I began scoring the piano part and then I hit another wall: I couldn’t figure out where the piano line was going. It didn’t make any sense to me. I grew frustrated. My view of art — any art — has always been that it’s a craft. So whether I paint a canvas or carve a sculpture or write music, there are techniques I can use to create a perfect piece of art. I have tenaciously clung to that view, even though I have abundant evidence that it’s not completely true. When I sat down with Psalm 23, I planned out my approach and knew what style I wanted. I knew what I wanted to do with the vocal lines. But instead of skillfully writing it all out, all I could do was sit and stare at the screen. Albert Einstein once said, “I never made one of my discoveries through the process of rational thinking.” It wasn’t enough to know the technique and to understand the craft. I needed an epiphany. The word epiphany comes from ancient Greece, and it means a manifestation, or a striking appearance. An epiphany usually occurs not when you’re looking for it, but often at the most unlikely of times in the most unlikely places. Sometimes it’s not even clear what you’re even looking for. I used to ride my bike from my home in Easthampton to my job at Mountain Park. I was writing a lot of music at the time, with several pieces in various states of completion for a planned recording. I can still vividly recall where it happened. I was heading south on Route 5 by the old coal power plant, when suddenly an entire song filled my head, a new one, something that I hadn’t even before considered. The previous evening I had a bizarre dream in which my sister and I walked into an old barn-like performance area. It looked like it was sometime in the 1950s. And there on a makeshift stage was a young Elvis Presley. I told my sister (who’s a big Elvis fan), “I have a time machine! We can get his autograph, return to the present time and sell it! We’ll be millionaires!” There I was on my bicycle, peddling away, when suddenly that dream became a fully-formed song flowing inside me. I had no paper or pen. I had no recording device. I hadn’t planned for it. It was not the best time for that epiphany. And so I began singing it out loud. Over and over. The rhythm of the song became the rhythm of my pedaling. For the following half-hour, up the hilly road alongside the Connecticut River, I sang the tune over and over and over, terrified that if I stopped singing, the entire piece would vanish forever. I pedaled over to the makeshift office underneath the merry-go-round, grabbed a pen and paper and began frantically writing out the song. It eventually became the title track to my recording, giving a form to the entire collection, unifying all the other ideas that had been floating around in my head. That’s epiphany! It’s a sudden flood of the Holy Spirit. Often, the circumstances don’t make sense. The timing can be inconvenient. But when it happens, there’s no mistaking its importance. It’s like the words of Psalm 29: “The voice of the Lord is over the waters; the voice of the Lord flashes forth flames of fire; the voice of the Lord causes the oaks to whirl.” An epiphany often can be that earth-shattering. In the New Testament (Acts 19), we hear how Paul had traveled to Ephesus, a city in Turkey on the Mediterranean. He happened to find about a dozen disciples. How did he just happen to find those believers in Christ out of the thousands of other people in the city? Well, how did I hear a fully formed song in my head? It’s as if some sort of spiritual alignment happens. And although the twelve said they were believers, they didn’t have their own epiphany until Paul laid his hands on them. I can imagine them wandering about without a purpose, much like I had been doing on my bicycle, just heading off to another day at work. But at that fateful meeting with Paul, they were transformed by the Holy Spirit — the manifestation of God that’s synonymous with epiphany — into true disciples who remained with Paul for the rest of his journey. Probably the most well-known spiritual alignment was the journey of the magi to find the Chosen One. The magi were basically astrologers tracking a curious stellar alignment. They weren’t entirely sure exactly where they were going or who they would find. But they placed their trust in forces they couldn’t understand. When they finally found Jesus, by then about two years old, it was a revelation, a moment when for them the entire future of the world would change. Epiphany has also been linked with the miracle at the wedding in Cana, when a still-young Jesus turned water into wine and foreshadowed his own death. And Epiphany is associated with Jesus’ baptism, which was certainly a “striking appearance” for John the Baptist. Now some might say that there is no divine intervention in any of this. In the example of my own epiphany with the song, it could be argued that my mind had been working in the background on various songs for weeks and, like baking a cake, the time was right for the idea to come out of my mental oven. But that doesn’t explain how an entirely new song appeared to me, fully formed, that had nothing to do with the other songs I was working on. I can’t find any rational explanation of how that could happen. But I can find a spiritual one. God is amazingly, shockingly generous. God in my experience does indeed provide. But the caveat to this is that God will provide only that which is earnestly wanted and needed. And sometimes it can be difficult to understand the difference between wants and needs. A want is something that would be nice to have. A need is a more desperate desire, a desire that somehow always connects back to God. We as mortals are all interconnected; actions we take in our community can have an impact on everyone involved. And that impact can ripple out to others who we thought had no connection to us at all. God seems to bestow epiphanies in situations that have a ripple effect on humanity. For example, author Chris Benguhe in a Saturday Evening Post article told of a seemingly grim Chicago day in 1972 when firefighters responded to a blaze in an apartment building. When they arrived, the building was engulfed. One of the firefighters, a 24 year-old man named Jacob, noticed that the higher he and his partner progressed into the building, the worse the conditions became. But he had a strange nagging feeling that someone was on the fifth floor. He didn’t know why he thought that. He was about to turn back when he heard the cries of a woman who came running out of the smoke looking for her child. Sure enough, Kris, a 7 year-old boy, was somewhere unconscious on the fifth floor. Jacob and his partner rushed up the stairs. But the flames became overwhelming. Jacob’s partner motioned for them to go back, assuming all was lost. But for some reason, Jacob dashed forward into the flames and found the boy unconscious, lying in one small section of the floor that somehow wasn’t on fire. Jacob scooped up the boy and fled back down the stairs. A few weeks later, the boy and his mother visited Jacob at the fire station and said that they would repay him a life. Jacob thought that was a touching sentiment, but gave it little other thought. Jacob did stay in touch with Kris, though, and each year he took Kris to a Chicago Cubs game. Twenty years later, Jacob developed diabetes and end-stage kidney failure. There were no compatible donors available. When Kris called to arrange for their annual baseball outing, he was shocked to hear of Jacob’s condition. Within an hour, Kris was at Jacob’s door. He was a perfect match as a donor. “I’ve got two kidneys,” he said to Jacob, “and you can have one.” The operation was successful. Kris went on to become an English teacher and Jacob retired to become a counselor for inner-city children. And so the impact of their actions continued to ripple outward. What would have happened if Jacob had not instinctively run into the flames? What would have happened if Kris hadn’t called to ask about his yearly outing? And more importantly — what drove them to act the way they did? You might say that Kris called each year anyway, so it wasn’t anything unusual. But if he had waited several more weeks it may have been too late. Jacob had his epiphany in the fire, and the choice he made at that time changed his life in ways he could never have imagined. That is the nature of an epiphany. It brings about a transformation. That’s what the magi discovered. That’s what the guests in Cana discovered. So there I was in the comfort of my den, wracking my brain, agonizing over a piano part that simply wouldn’t come. I tried to force it out. I put notes on the page that should have done the job. But the music was lifeless. So I tried different notes. And that was worse, not only lifeless but cacophony as well. I called it quits for the night, and the next night I was back at it. It was less like creating music and more like a military assault. I was forcing notes onto the staff like soldiers being sent into battle, knowing full well that a massacre was on the horizon. I did this night after night, with no better result, for two straight weeks. I felt I had to finish the piece, that I was a failure if I couldn’t do it on demand. Then something happened. It was like a shade being raised, letting in the morning light. I suddenly realized that I was writing a hymn, a song to God — and for God. So I closed my eyes and said a little prayer of sorts. If this was something God wanted me to finish, then with His help I would finish it — not on my schedule, but on God’s. It was yet another reminder that I’m not really in control of every part of my life. If I simply trusted in God, the epiphany would come. So I put away my music and moved on to other things. Several days later I sat down in front of the computer and impulsively pulled up the hymn — and suddenly everything fell into place. I began writing, and it was no longer work. I wasn’t forcing notes onto the page. The piano part simply began to flow, writing itself, and it finally seemed so simple. It all made sense. Within a few hours, the piece was completed. Not all epiphanies have to “flash forth flames of fire”. What did it matter whether I completed the piece? Did the axis of the world suddenly shift as I penned the last note? Nothing seemed to change. But God sees more than I could ever imagine. An epiphany begins a long journey, just as with Jacob, and often the destination isn’t clear. In those times its helps to remember that we’re not really in the driver’s seat. I don't need to create epiphanies on demand. All I need to do is trust, and allow God to work in His mysterious ways. And that is beautiful music to hear indeed. August 9, 2015  The late comedienne Phyllis Diller was probably channeling Paul and his letter to the Ephesians when she was asked what the secret was to her long marriage. Her reply: “Never go to bed mad. Stay up and fight.” Although Paul doesn’t advocate going to battle, he does caution against drawing out anger. Anger is often perceived as a dangerous emotion in our society. If left to run rampant, anger can seem to cause indescribable damage, both physical and emotional. Anger can often seem to be intense and unstoppable. The word brings to mind screaming lunatics, armed radicals, vengeful lovers, horror movie scenarios. Many people go out of their way to avoid dealing with anger, either their own or someone else’s. It has a pretty bad rap — in our culture. Other cultures deal with anger a bit differently. For instance, Buddhists look at anger as one of three poisons (the others are greed and ignorance). We often tend to think of anger as something caused by someone or something else. So for instance, if I’m cleaning my gutters and the ladder tips over and I fall off, I get mad at the ladder. “Stupid ladder! What a piece of crap!” It’s all the ladder’s fault. But the Buddhist view is that anger is an emotion that you create. There’s no external cause, only an internal trigger that you can either respond to or ignore. If I fall off that ladder, I could choose to simply pick myself up, figure out what went wrong and fix the problem. Getting angry accomplishes little except to deflect the problem off of myself and lay the blame elsewhere, in this case my poor choice of how I set up the ladder. Humans often want to think “the fault lies not in ourselves but in our stars”, and anger can be a way to avoid responsibility for our choices. I frequently get angry at myself. In that ladder scenario, I wouldn’t necessarily blame the ladder, but I’d blame my own stupidity at not recognizing the problem before it happened. Either way, anger has no effect on the outcome and doesn’t help me correct my behavior. Anger can also be used as a psychological tool to manipulate people, to instill fear in others — and through that, control them. Paul makes an interesting distinction in this passage from Ephesians: “Be angry but do not sin; do not let the sun go down on your anger.” He doesn’t treat anger as something bad or something to be feared. And it’s not a sin to be angry, though Paul implies that anger can lead to sin. Anger might cause someone to act rashly and lead to further problems. Listen to this further distinction he makes: “Let no evil come out of your mouths, but only what is useful for building up.” When anger (or any other emotion) is used to manipulate, it’s not very constructive. Anger, in fact, is often used to tear down another person. Paul’s statement is similar to the Chinese proverb, “If you are patient in one moment of anger, you will escape a hundred days of sorrow.” Anger can be especially difficult to deal with when it’s directed toward another person, because it can often prevent you from communicating with that person, which in turn prevents you from resolving the problem, which in turn can create more anger. It’s a vicious circle. But the only person who can break out of that circle is you. My strategy is usually avoidance. If I’m angry with someone, I simply stay away from that person so that I don’t have to confront my anger. The truth is that the only way to resolve the anger is to communicate with that person — and I said “communicate”, not “confront”. I read about a recent incident where a driver cut off another driver in order to turn into a Dunkin’ Donuts. The offended driver drove into the parking lot, got out of his car, walked over to the drive-up window and began beating up the driver who cut him off. Naturally, the situation didn’t end well. You can’t build up or repair a relationship by assaulting someone. So how do you communicate anger constructively? As the Buddhists know, you can’t deny anger. Denying or avoiding it only makes it worse. There are tactics you can employ to help diffuse anger. In the past, when I got angry I’d spew out a string of expletives. But I gradually changed my behavior and now make sounds like an angry cat which, like me, is a bit odd but less offensive. I generally don’t hide my anger, but I don’t let it run wild either. The most productive thing I’ve learned to do is, if I’m with someone, simply say, “I’m feeling really angry right now.” That simple admission of an emotional state I’d rather hide, usually helps diffuse things. I’ve talked about Buddhism. Now let’s look at the Bible, where there are numerous instances of anger. In fact, it’s mentioned over 300 times. In both the Old and New Testaments, God shows anger with his people. In Psalm 74, the writer asks, “Why does your anger burn against the sheep of your pasture?” In Psalm 90 he says, “Truly we are consumed by your anger, filled with terror by your wrath.” Jeremiah writes, “The blazing anger of the Lord has not turned away from us.” Remember how God in anger banished Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden, cleansed the earth of all people but Noah and his family, and repeatedly punished the people of Israel for their sins. But though there are numerous instances of God’s wrath, there are an equal number of instances of compassion. From Psalm 103: “Merciful and glorious is the Lord, slow to anger, abounding in mercy.” And from Ecclesiastes, this very Buddhist phrase: “Do not let anger upset your spirit, for anger lodges in the bosom of a fool.” The god of Abraham and Moses, the god whom Jesus called Father, is at heart a god of forgiveness. Although God may be angered by the actions of His people, sincere contrition always diffuses the anger. Just as a parent will always forgive a child, God always forgives us. So perhaps that’s the key to managing anger. It’s not about suppression. It’s not about denial. Perhaps all that needs to be done is that someone needs to be forgiven. Maybe it’s the person you think made you angry. Maybe it’s yourself. Remember the famous example that Luke mentions: Jesus says, “If your brother sins, rebuke him; and if he repents, forgive him. And if he wrongs you seven times in one day and returns to you seven times saying, ‘I am sorry,’ you should forgive him.” That passage is remarkably similar to Matthew’s account, when Peter asks Jesus how many times he should forgive someone — seven? And Jesus responds, “Not seven times — but seventy times seven.” You can’t remain angry with someone you’ve truly forgiven. Paul concludes the letter to the Ephesians with these words: “Be kind to one another, tenderhearted, forgiving one another as God in Christ has forgiven you. Therefore, be imitators of God as beloved children, and live in love.” Life is not about the angry moments, because anger is about destruction and from anger can spring many other unhealthy attitudes. Life is about forgiveness and love, which heal injuries and build up relationships. That is the grace you give to those who hear. Incidentally, the Chinese character that you see above is ting, meaning “to listen”, and it’s an interesting construction comprised of four separate symbols. At the top, ears and eyes are joined by the symbol for undivided attention. And underneath them all, holding them all up, is the symbol for heart. For only by opening our hearts can we truly receive the grace we need to understand the words we need to hear. JULY 1, 2015 Stephen Sondheim turned 85 this year. For most of my student life, he was a defining figure, someone I wanted to emulate. But it didn't begin that way. My first exposure to Sondheim was covert; I didn't know who he was or what he had done. When I went to Holyoke Community College as a freshmen theater student in 1976, the Drama Club had just finished a production of A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, the first show for which he had written both music and lyrics. Most of the students at that time were obsessed with the musical Company (that and Chorus Line, which I loathed). And anything the other students liked, I reflexively hated. It wasn't until 1979 that I began to pay more attention. I was at a family picnic at Mountain Park. During that time, I had just discovered Carl Orff's Carmina Burana and was obsessed with its use of huge orchestration, erratic rhythms and dissonance. I was sitting on the park's Sky Ride, gliding over the picnic grove, when I heard someone's radio playing at our table. It was tuned to National Public Radio (which I listened to frequently). It sounded like the opening of the Carmina. But as I continued listening, it became obvious that it was a completely different piece. The ride pulled me to the far end of the grove and the music faded away. Then the ride reached the turnaround, bringing me back over the table. I could hear that it was still the same piece playing, though it had a much different timbre. When the ride finally ended, I rushed down to our table and listened. It sounded like a modern classical opera, though I usually didn't like opera. The music and lyrics were lean and mezmerizing, always driving the plot forward. I wasn't quite sure what the plot was at that point, since I had caught it in the middle. But I knew someone was trying to murder someone else. After about a half-hour, the announcer interrupted the piece: "You're listening to a recording of Stephen Sondheim's new musical Sweeney Todd: the Demon Barber of Fleet Street." The next day I went to Main Street Records and picked up a copy of the soundtrack. It was a double-LP set, with lots of photographs on the inside and a booklet with the complete libretto. I went back to my apartment and listened to it. And then I listened to it again. And again. I was impressed with the performers, none with whom I was familiar. And the story was a sweeping emotional melodrama. But what really grabbed me were the music and lyrics. I had looked upon musicals like Mame and The Pajama Game as treacle, nice attempts at creating radio-friendly songs for my parents. But Sweeney Todd sounded like REAL music to me. And you couldn't simply pull songs out of the musical and expect them to stand on their own; the entire score and libretto were inextricably intertwined with the story. Sondheim's lyrics were brilliantly written, simultaneously clever, funny and terrifying. I hadn't heard as good a wordsmith since Tom Lehrer. I saved my pennies and in 1980 took a bus to New York to see the original Broadway production of Sweeney Todd. It was in the massive Uris Theater. The recording had a haunting intimacy to it. The Uris, on the other hand, was more like sitting in a football stadium. The stage was cavernous. It's backdrop was a black-and-white drawing of old London. The perimeter of the stage was filled with all sorts of moving machinery: gears, levers ... it was distracting. The big setpiece was a cube that was wheeled on by chorus members and acted as the pie shop or the bake house or Mrs. Lovett's living room, whichever way they oriented it. And there was a huge bridge spanning the stage that moved forward and back. Because of the size of the space, the performers had microphones, a new wireless system that caused strange feedback when actors were too close to each other. The whole production reminded me of Brecht's concept of epic theater, preventing me from becoming emotionally involved with the story. It was the exact opposite of my reaction to the recording (which IMO is still the best rendering of the musical). After that disillusioning experience, I did a little more research on Sondheim. I was still not mature enough to comprehend Company, though I really liked the song Ladies Who Lunch. The music and lyrics for Forum were cute, but nothing that grabbed me. His work on West Side Story was primarily overshadowed by Bernstein. It wasn't until I moved to New York that I began to truly appreciate Sondheim's genius. For his 50th birthday, New York's public radio station aired a 3-hour tribute to him, with interviews and exerpts from all his shows. They also played some rare cuts from his one foray into television, the eerie musical Evening Primrose. I recorded the broadcast onto a cassette tape and listened to it often after that. I was struck by his consistently meticulous lyric crafting. I found songs from Follies especially fascinating because they had an eternal quality to them. It sounded as if songs like Broadway Baby and Losing My Mind had always existed, written long ago and only recently found. And I knew how difficult it was to achieve that quality.

The host of the radio special also mentioned that a new Sondheim

musical, Merrily We Roll Along,

was in production and would soon debut. Coincidentally, a student

in Columbia University's theater program asked me if I wanted to go

with him to audition for it. I figured that would be an

interesting adventure, so I got my head shot and resume together and we

headed to the lower west side. The auditions were in a fairly

non-descript building. We were given a number as we

entered. I was given something like #386. There were a LOT

of people auditioning. Actually, "auditioning" is a

euphemism. This was a classic cattle call. The producer

(the famous Harold Prince, who produced almost all of Sondheim's shows)

and the casting director were after a certain look. So we stood

in an interminable line, winding through corridors and up stuffy

staircases. Hours later, we arrived at the casting room, an

equally non-descript place. The casting director was standing

behind a long table. Sitting next to her with his chin propped on

his hand (and looking supremely bored) was Harold Prince. As we

approached, he stood up and said to her, "I'm going for a coffee" and

left the room. I walked up to the casting director and handed her

my packet. She quickly looked at me, then it, and said, "Too

old. Thank you for coming." If

God told you exactly what it was you were to do,

you would be happy doing it no matter what it was. What you’re doing is what God wants you to do. Be happy. |