|

| Mountain Park in Holyoke, Massachusetts began life in 1894 as a trolley stop at the halfway point up to Mount Tom. It was a simple place with gardens, a carousel, roller coaster and a few concessions. In 1929, Louis Pellissier, who ran the Holyoke Street Railway Company (which owned the park) embarked upon a major expansion of the midway, adding a half-dozen new rides and several concession buildings. Between that period and the 1940s, the park's first two fun houses were added. Apparently, they were both walk-thrus and sat side by side. The southernmost one was called Loop the Loop, and possibly had a rotating barrel in it through which patrons had to walk. That fun house was later converted into a ride-thru dark ride called Laff in the Dark, which was a common name used for many dark rides. It was a single-level ride with Pretzel-made cars. There were "falling" barrels that tumbled toward riders. And the finale of the ride was a loud horn blast. The design reflected that of similar rides at other amusement parks. The lettering had an Art Deco look to it, with a crescent moon placed between "the Dark." In 1952 John Collins, who owned Lincoln Park in Dartmouth, Massachusetts, purchased Mountain Park from the Holyoke Street Railway. This was the beginning of the park's renaissance and would lead to its golden years. The dark rides and fun houses that were installed in the following years were integral to the park's success. Between 1953 and the park's closing in 1987, the small midway featured no less than six different fun houses and dark rides. In the late 1970s through the early 1980s, there were two dark rides and a walk-thru fun house operating simultaneously! All of the rides were designed and themed by three individuals. One was Edward Leis, a brilliant engineer who freelanced with National Amusement Devices. He is probably best remembered as the designer of Mexico's Montana Rusa roller coaster. Leis worked for the Collins family at both Lincoln Park and Mountain Park, and built Lincoln Park's Comet roller coaster. He rebuilt the coaster at Mountain Park as well, and he also lended his expertise on the construction of many buildings, including the dark rides and fun houses. The man most responsible for the unique look of not only the fun houses but also the entire park was Dominic Spadola. This energetic little man from Rhode Island had done work for that state's Crescent Park, Rocky Point, New Hampshire's Pine Island Park, Lincoln Park and Whalom Park in Fitchburg, Massachusetts. He created colorful and fantastical figures out of plywood, homosote, celastic and fiberglass. He helped develop the angular, twisted pastel facades of the parks' buildings. He created enormous clown faces that graced buildings and signs. The stunts he designed for the Mountain Park rides had a nightmarish but cartoonish quality to them. It was a tricky balance to achieve: something that would thrill adults but not terrify children. In the late 1950s, renovations began on Laff in the Dark. Leis re-worked the interior and created an upper level. Six new cars were purchased. The transmissions of the new cars were modified to allow a swift and sure climb to the top. Each car had a differential gear in the rear axle and a lot of torque. They came with what appeared to be a colorful primitive ritual mask molded into their front in fiberglass. The ride was themed as an African jungle and called Mystery Ride. The letters on the building were placed on motorized shafts and rocked back and forth. Below the letters was the upper level, which featured a brief U-turn over the loading station. On each side of that were two odd figures with large ears and noses and gum-stick bodies that rocked back and forth. Below that was the station. On the walls next to the entrance and the exit doors were six brightly-painted masks, sporting hideous grins. The masks also rocked back and forth. The clash of colors, the stylized paintings of jungle foliage and animals, the constant movement all over the building – it was a tour-de-force for Spadola and a feast for the eyes. For the interior, Spadola created a wide variety of three-dimensional fantastical scenes, from Hell to stereotypical African natives. The Mystery Ride didn't last very long, however. In 1963, to capitalize on a renewed interest in dinosaurs, the ride was re-themed to the prehistoric creatures. The track was lengthened and Leis created an extension of the upper level out over the midway. On either side of the extension, Spadola created two massive dinosaurs. The one on the left was poised with its front and rear legs up, as if it were about to stomp the patrons. The one on the right stood erect with its arms outstretched. Both had red flashing eyes, large sharp teeth and jaws that opened and closed. The rocking masks remained, but the walls around them were repainted to look like a cave. Spadola also recreated images from the children's book "Where the Wild Things Are" by Maurice Sendak. The building itself was covered with lumpy celastic over chicken wire and painted to look like rock outcroppings. Roger Fortin, supervisor at the park for nearly forty years, was the third man responsible for the construction of the dark rides and fun houses. He clearly recalls one day when he was building the rock surface with Spadola. It was in November of 1963, and it was bitterly cold. The temperature seemed more extreme because they had to soak the celastic in acetone to make it pliable. Another worker walked over to them about 4:00 in the afternoon to tell them that John F. Kennedy had just been shot. Seven years before that, Kennedy had celebrated his 39th birthday at Lincoln Park. One amusing renovation was to the lettering. The ride was renamed "Dinosaur Den," which had the same number of letters as "Mystery Ride." However, the letters weren't spaced the same. Since they were all attached to motors bolted into the building, it would have been too much work to re-arrange them. New lettering was simply placed over the old. So for over twenty years, the name of the ride was "DINOSAU RDEN." The ride was a big success for the park. In fact, it was so successful that they ordered a seventh car to increase capacity. Spadola used the bas-relief on one of the original cars to make a mold of it. Then he re-created the bas-relief in fiberglass on the new car. "On a busy, busy day," said Fortin of the cars, "you could have them all going on the track…it was timed perfectly." As far as my memory can recall, the circuit began with the car curving to the right and slamming through a set of heavy wood doors. The car immediately turned left and after a few yards slammed through another set of doors with a tiger painted on them. The car would then turn sharply right 90 degrees and begin heading uphill. The first stunt was on the right. The car swung again to the right, about 90 degrees, passing an emergency exit and continuing uphill. Another stunt was on the left. Another right turn, about 90 degrees, was met with the next stunt on the right. The car would turn 180 degrees to the left. Another stunt would be on the right. Then after turning 180 degrees to the right and passing a stunt on the left, the car leveled off. It would slam through a set of doors, then another set, travel out onto the overhang, pass by a stunt at the center of the overhang, swing around to the left 180 degrees and then slam back through another set of doors. After passing through yet another set of doors, the car began its descent. It passed by a stunt on the left, turned to the right about 180 degrees, passed a stunt on the left and then swung around 180 degrees to the left. Another stunt was on the right, as was an emergency exit down a set of stairs. The car would turn 90 degrees left and pass by an enormous stunt on the right. It was about 20 feet long and dropped down through the floor. Then the car swung 180 degrees to the left, passed by a stunt on the left and leveled off. A 90-degree right turn revealed a stunt on the right. The car was then traveling at the far right end of the building. Then another 90-degree turn to the right was met with another set of doors. After passing through them, the car was traveling in a sort of tunnel. Looking off to the left, you could see the station and midway. Looking to the right, you'd see an animated stunt. Originally, it was a caveman dunking a cavewoman into a big pot. The last operational stunt there was Frankenstein, which bobbed up and down behind a stone wall. After passing that stunt, the car collided with another set of doors, turned left 180 degrees, went through more doors and back across the tunnel area, only this time a little closer to the station. More doors were hit. The car took a sharp turn to the right into the final set of doors and then was back at the station. My father ran the ride for many years. He tired of having to lean forward to press the control panel buttons that would advance the cars. So he fashioned a wooden rod 17" long. It resembled an enormous screwdriver. It had a handle on one end and a small cylinder at the other about the size of a short stack of quarters. He could then sit back in comfort and use the rod to press the buttons. Over the years, the stunts changed. As vandalism increased, there were fewer and fewer three-dimensional stunts installed. Spadola used florescent paint on plywood and homosote cutouts, and these were placed safely behind metal screening. One of my favorite stunts was installed in the 1970s. It remained right up until the park's closing. It depicted four children holding flowers. Above them, in psychedelic 1960s lettering, hung "Flower Power." I've long considered this to be the most uniquely terrifying stunt ever placed in a dark ride. Most of the other stunts depicted undecipherable figures, fantastical and seemingly hastily drawn characters that only occasionally resembled creatures you'd encounter in the real world. Spadola included a couple of scenes of Hell (one of his few recurring "themes.") Very few people, except for small children, found any of these scenes scary and that was in keeping with the family-park atmosphere. A "hi-tech" sound system was added in the late 1970s. A series of eight-track tape players were triggered by rollovers on the track. The system was difficult to maintain, but amusing when it worked. After the park closed, I remained on the grounds as a watchman. The Dinosaur Den was a prime target for vandals who would come up to the closed park with bolt cutters and sledgehammers. Their only intent was to destroy things. I was constantly boarding up and fencing off the ride, trying to protect it. Eventually, a traveling carnival bought the cars and the track. They tried to remove the huge dinosaurs, but underestimated their weight. They succeeded only in dropping one onto the midway. They left it there, where weather and vandals took their toll. I left my watchman job in 1994, and a few months afterward vandals burned the Dinosaur Den to the ground. Only the foundation and the structure of the overhang remained. Now the area is almost unrecognizable; the overhang has rusted out, and nature is reclaiming the first dark ride that thrilled generations of guests on the mountain.

The fun house also existed at the park when the Collins family bought it. Leis and Spadola made changes to it every few years, so that it seemed to be in a constant state of flux. For many years, it was decorated with the subtitle "It's fun to get lost." It sat just to the right of the Mystery Ride. Like Laff in the Dark, it was originally a one-level amusement but was soon expanded to two. Spadola worked his magic on the facade, which was made of wood, homosote, tin and fiberglass. Big three-dimensional letters adorned the front. A later incarnation featured a large bas-relief cartoon labeled, "Magic Carpet." It depicted a comical group of middle-eastern men on a flying carpet. The entrance was through a short corridor on the left. There was a railing made up of brightly-painted 2x4 wood that formed the word "Maze." (That technique of forming words in wood fencing was commonly used at the park.) The corridor led to the beginning of an elaborately constructed mirror maze. The maze was put together from eight-foot-high six-sided wood posts, built of standard 1x3 lumber surrounding a wood core. There was a gap where the pieces of 1x3 met. The layout was drawn up on a blueprint. Then the posts were affixed to the wood floor, and 4-foot by 8-foot panels of glass and mirrors were positioned between the gaps in the posts. If I remember correctly, the mirrors were placed at 45-degree angles to each other. It was possible to re-configure the maze by re-arranging the mirrors and glass into different gaps in the posts. A path led between the panels and brought patrons eventually into a "tipsy room," where the floor was raised up at one end and lowered at the other. Railings forced patrons to travel back and forth until they reached the high end of the floor. Patrons would emerge at the left side of an overhang above the entrance. From the midway, you could see only legs as people passed through. There were air jets in the floor at that point, naturally, to blow skirts up. Then patrons would head to the back right section of the building where there was a separate little "shed" structure tacked on. That housed the "Magic Carpet." It was an elevated platform with a bench. The patron would sit on the bench. An operator would throw a lever and the bench would drop, dumping the patron on to a large motorized conveyor belt. The patron would be unceremoniously dragged down to the floor below. The Fun House exit was then to the patron's right. As time passed and patrons became more litigious, the Magic Carpet grew to be a liability. It wasn't necessary to ride the Magic Carpet; patrons could simply walk past it to the exit. But more and more people were starting to sue the park for injuries relating to it. So Roger Fortin removed the Magic Carpet and added another tipsy room there. This one was built like a jail cell with simple 1-inch-diameter scrap iron pipes welded to iron frames and attached at the ceiling and the floor. "It just gives you that much more illusion when you're walking through," Fortin said. It was all lit with blacklights. The Fun House was very popular. But over the years maintenance became more difficult. The floor began rotting out. So in the late 1970s it was dismantled. In its place, Spadola and Fortin built a single-level ride-thru attraction, The Pirate's Den. This was the last dark ride built at the park. The cars were stock Pretzel purchased new. Dominic and Roger came up with a blueprint of the track. Pretzel then took the blueprint and custom-built the track in sections, which were then shipped to the park ready for assembly. To make sure the floor wouldn't rot this time, Fortin made a new floor of poured concrete. Then he found out that Pretzel insisted that their cars be run only on a wooden floor. So he fabricated a separate running track out of wood and affixed it to the concrete. The spectacular ballyhoo for this attraction was a huge pirate ship that spanned the entire length of the building. It was positioned above the loading station. It sported a massive pirate's head and many cutout figures. To make sure kids wouldn't get out of the cars and run around inside the ride while the cars were moving, the front of the building sported three large windows that were opened during operation. Thus, the ride operator could see into the ride at all times. That deterred any hanky-panky the kids might consider. One obvious result of this was that during the day, it was no longer a "dark" ride; light flooded the interior. But at night, the blacklights made the interior look spectacular and surreal. The layout was fairly simple: the car would leave the operator's station and turn 90 degrees to the right. It would knock open two big wooden doors and enter a long dark corridor that ran along the left side of the building. Upon reaching the back of the building (where there was an emergency exit door) the car would turn 180 to the right and head back toward the front of the building, passing by a big painted scene on the right. The car would then turn left and begin a zigzagging trip past the big windows. There was a scene of pirates digging up a treasure chest to the left. When the car got to the right side of the building, it swung around sharply to the left and headed back in the opposite direction, behind the diorama of the pirates digging treasure. There was a painting of a pirate next to a skeleton, and to the right, on the back wall of the building, was an enormous painting of pirates on an island. The car then turned 180 degrees past a stunt of a pirate bobbing up and down and then veered slightly to the right. The black wall in front of the car would light up and behind a Plexiglas window an enormous brown balloon would suddenly inflate, rising up from the floor. It had two eyes and sharp teeth and vaguely resembled a gorilla. It never failed to elicit shrieks of surprise and laughter. The car would then turn left sharply toward the back of the building. If you looked closely at that point you could see the one remaining vestige of the old Fun House: Fortin's second tilty room. It remained there intact behind metal screening. The car swung around 180 degrees to the right. And to the right was the final stunt: a devil that would bob up and down. The car would then turn right and slam through the big wooden doors to the exit. The Pirate's Den remained essentially unchanged over the years. The paintings had a curious unfinished quality to them, as if Spadola didn't quite have enough time. But the ride served its function as a pleasant family diversion. After the park closed, the ride (including the ballyhoo) was sold to Pirate's Fun Park in Salisbury, Massachusetts. The remaining structure at Mountain Park burned to the ground in 1994 along with the Dinosaur Den. The only thing that remained recognizable was Fortin's second tilty room.

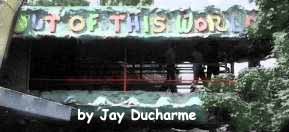

One of the most fondly remembered rides from the park was built in the late 1960s on a site formerly occupied by a workshop and a game concession next to the Play Land arcade. Spadola, Leis and Fortin transformed the building into one of the most spectacular walk-thru fun houses ever constructed: Out of This World. This ride was really dark. Most of the interior walls were painted gloss black. Spadola designed most of the layout with assistance from Leis. He created an enormous assortment of bizarre paintings and three-dimensional characters to populate the ride. The walls depicted planetary scenes with spacemen in suits and weird nightmarish creatures. There were also many whimsical characters. The entire ride itself was the ballyhoo: from the realistic rock surface of the building (again, celastic), to the giant flying saucer that seemingly had crashed into it, to the overhang (fronted by a giant lime green and pink robot) where patrons would walk out and around. Everything was dotted with intense colorful flashing lights. A peculiar combination of synthesized noises blared out onto the midway from the eight-track tape system, sort of like early "house" music without the beat. The journey began with entry into the saucer. You'd pass through a corridor with large rubber half-cones embedded into each wall, from the floor to about hip height. They'd alternate one on the left and one on the right. This was a gag used in many other fun houses. From there you'd enter a dark tipsy room. It had a black-lit wall with a painting of astronauts on the moon, surrounded by alien creatures. You'd then progress up a ramp and come out on the south side of the overhang. Advancing counter-clockwise around the overhang, you'd encounter various moving platforms. On the floor of the turnaround was a spinning metal disk that Fortin made. "It would help you, turn you around the corner," he said. "But the insurance people didn't like that." Next were wood planks on the floor that moved forward and back. Heading back inside the building, the corridor turned 90 degrees to the right. You'd then be directly over the saucer. There was a lookout onto the midway as you passed over air jets in the floor. You'd take a left and follow a ramp downward to the back of the building. There was another tipsy room, which led to a corridor that brought you out the saucer. A small room was built near the middle of the ride from which an employee could watch the various corridors to make sure the patrons were safe. Naturally, there were always kids who wanted to fool around. Since the fun house was so dark, it was easy for kids to hide in the corners and surprise unsuspecting patrons. After several years, the moving platforms were locked down to appease the insurance companies. Eventually, there were so many complaints from patrons of being harassed by kids within the ride that in 1982 it was decided to modify the building. The floor of the overhang was kept, but as a roof for a coin-operated punching bag game. The lookout over the saucer was retained for show only and outfitted with some of the characters that used to populate the ride. It was the only reminder of the once-glorious fun house. The building itself was turned into a new arcade and stayed that way until the park closed. Some of the other figures could be found scattered around the midway, amusing and colorful statues somehow out-of-place without their home. After almost 100 years of fun Mountain Park vanished from Holyoke, taking with it some remarkable amusement creations. The Mystery Ride, Dinosaur Den, Fun House, Pirates Den and Out of This World were unique because of the creativity and ingenuity of Dominic Spadola, Edward Leis and Roger Fortin. Now their brilliant work is gone. Their rides were made in a time of simpler amusements, when scrap metal, wood planks, homosote and a little resourcefulness could be assembled into something that gave joy to generations. I treasure parks like Kennywood and Waldameer that are carrying on a tradition for a new generation of dark rides and fun houses that are simple yet thrilling for all ages. In the early 1990s, a man purchased one of the two robot statues and then drove around with it strapped to the roof of his car until vandals set it on fire. City youths took over the abandoned arcade, with its roof leaking and façade covered with graffiti, and used it as a skateboard arena until heavy snows collapsed the roof during the winter of 2000. Where there was once a thrilling work of art now sits a heap of rubble, indiscernible except for the roofline. If you look closely at the opening in the facade where the overlook was, you can still see the park's last remaining example of Spadola's work: an odd little spider-like creature from Out of This World that somehow escaped being covered with graffiti. And it's strange, but it looks as if there's a tear coming out of its eye. This article was originally written for Laff in the Dark, a website devoted to dark rides and funhouses. I'm grateful that Roger Fortin was willing to share his thoughts with me. I'd also like to thank Bret Malone, Tim Champagne and Maureen Costello for their kind assistance in keeping memories of Mountain Park alive. POSTSCRIPT: In 2002, a few years after I had written this article, a massive fire at the park leveled most of the remaining buildings including the oldest standing structure, the carousel pavilion. Shortly afterward, bulldozers flattened anything left standing. |